Last Updated on December 31, 2025 by Maged kamel

Parallel Axis theorem for Iy, Polar Moment of Inertia.

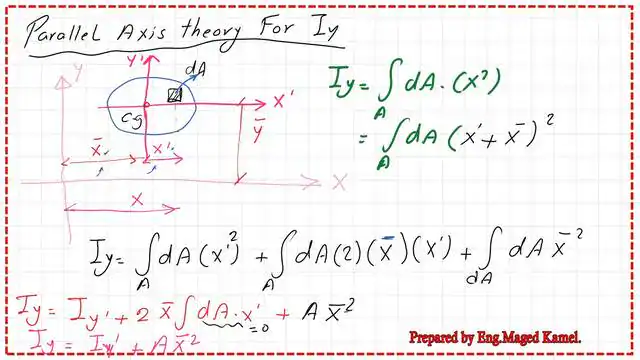

Parallel axes theorem proof for Iy.

We are going to talk about the parallel-axis theorem for Iy. We have two external axes again. x and y. We are going to choose a small Infinitesimal area. We call it, dA, and x ‘ and y are two axes passing through the CG of the area. The distance from the CG to the y-axis is called x̅. while the horizontal distance between the CG of the dA and y’.

The horizontal axis passing by the CG is called x’, and y̅ is the vertical distance from the axis x’ to x.

If we are going to estimate the moment of inertia about this y-axis. The ∫ dA*x^2 distance x distance can be estimated as the sum of two components.

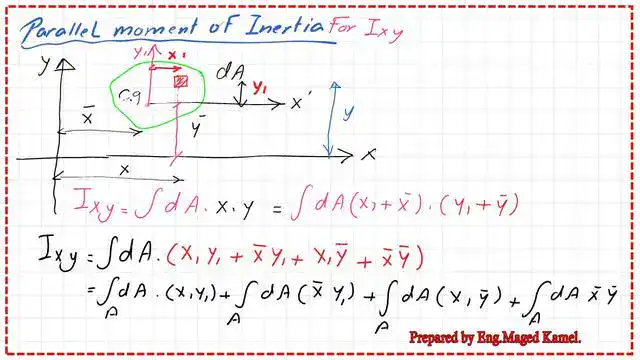

Parallel axes theorem proof for Ixy.

For Ixy, the product of moment of area is again the same area. We are going to introduce x’ and y’. These are two axes passing by the CG, and the external two axes, as usual, are x and y. The distance from the CG is y̅.

To estimate the product-moment of area, we need to integrate by multiplying dA by x, the horizontal distance, and y, the vertical distance, for both the x and y external axes.

Similarly, as before, this x = x̅ + x’ and the y overall distance y̅ + y ‘. We put both items inside brackets, and then Ixy = ∫dA.

Then we multiply by x1* y1+ X1* y̅ + x̅ *y1 + x̅ * y̅.

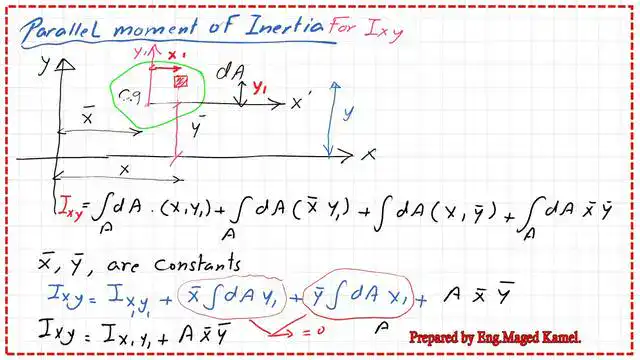

We are going to investigate each item and see what it resembles The ∫ dA*x1*y1=+ ∫ dA* x̅ *y1+ ∫ dA*x1* y̅ + ∫ dA* x̅ *y bar. Since x̅ and y̅ are constant distances, they will come out. dA*x1*y1, this is the product-moment of inertia about the CG., and we are going to call them Ix1y1.

The second term x bar will come out, we are left with dAy1+ y̅ will come out by the ∫ of dAx1, both these two terms, since the first moment of the area about x and y, are equal to 0.

These axes pass through the CG. Then, these two terms will be canceled. The last term, which is the ∫ dA* x̅ * y̅, will =A * x̅ * y̅ at the end, Ixy=Ix1*y1, and the product of inertia about two axes passing by the CG+Area x̅ * y̅.

What is the polar moment of inertia Ip?

For the Polar moment of inertia, this is a new expression. In polar coordinates, the moment of inertia is the sum of the moments of inertia about x and y, and this is considered a constant.

What does it mean? It means that for any two arbitrary orthogonal vectors, the angle between them should be 90 degrees. At first, the x’ and y’ axes pass through the CG; the I polar = Ix + Iy = Ix’ + Iy’.

The moment of inertia, if you are going to discuss the CG, is Ix + Iy = Ix1 + Iy1.

We define I_polar = I_x + I_y, so we can write I_x1 + A*x̅ + I_y2 + A*y̅. Selecting any two orthogonal axes that pass through (0,0) is also possible. We can call them x & y, or X and Y, then the I polar will again be equal to the sum of Ix and Iy.

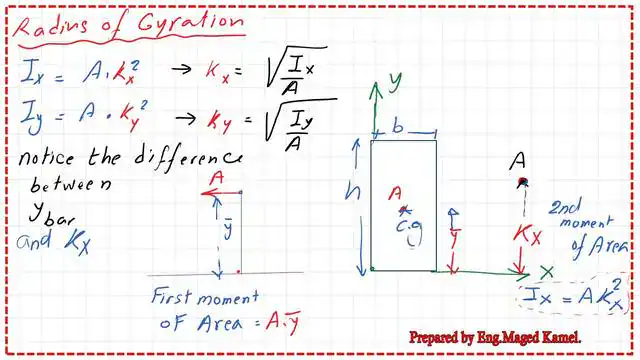

What is the radius of gyration for x and y axes?

There is another term, the radius of gyration for Ix = A* kx^2, so we can get an expression: kx = sqrt (Ix/A). Similarly, Iy=A*ky^2, which means that ky=sqrt (Iy/A). We will assume that the area, for example, of a rectangle is concentrated at its CG.

We will find that when the area is concentrated at the center of gravity, the first moment can be estimated as the product of the area and the vertical distance to the x-axis, y̅.

The difference between y̅ and k x lies in that the location of the point will be considered changed, and the multiplication of the area *kx^2 will produce the second moment of area, which is why Ix =A *kx^2 after considering the concentration of area.

You can download and review the content of this post through the following pdf file.

For an external resource, Engineering core courses, the moment of inertia.

This is a link to my playlist on YouTube.

For more details on the radius of gyration, see the wiki.

Next post: Moment of inertia Ix – What are the methods to estimate for the rectangular section?